Neste tutorial, você aprenderá a usar Python com Redis (pronuncia-se RED-iss, ou talvez REE-diss ou Red-DEES, dependendo de quem você perguntar), que é um armazenamento de valor-chave na memória extremamente rápido que pode ser usado para qualquer coisa de A a Z. Veja o que Sete Bancos de Dados em Sete Semanas , um livro popular sobre bancos de dados, tem a dizer sobre o Redis:

Não é simplesmente fácil de usar; é uma alegria. Se uma API for UX para programadores, o Redis deve estar no Museu de Arte Moderna ao lado do Mac Cube.

…

E quando se trata de velocidade, o Redis é difícil de vencer. As leituras são rápidas e as gravações são ainda mais rápidas, lidando com mais de 100.000SEToperações por segundo por alguns benchmarks. (Fonte)

Intrigado? Este tutorial foi desenvolvido para o programador Python que pode ter zero ou pouca experiência em Redis. Abordaremos duas ferramentas ao mesmo tempo e apresentaremos o próprio Redis, bem como uma de suas bibliotecas de cliente Python,

redis-py . redis-py (que você importa apenas como redis ) é um dos muitos clientes Python para Redis, mas tem a distinção de ser anunciado como “atualmente o caminho a seguir para Python” pelos próprios desenvolvedores do Redis. Ele permite que você chame comandos Redis do Python e receba de volta objetos familiares do Python. Neste tutorial, você abordará :

- Instalando o Redis da fonte e entendendo o propósito dos binários resultantes

- Aprender uma pequena fatia do próprio Redis, incluindo sua sintaxe, protocolo e design

- Dominando

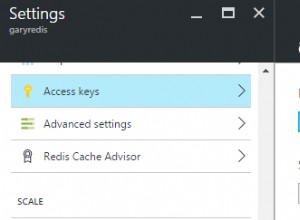

redis-pyalém de ver vislumbres de como ele implementa o protocolo Redis - Configuração e comunicação com uma instância do servidor Amazon ElastiCache Redis

Download gratuito: Obtenha um capítulo de amostra do Python Tricks:The Book que mostra as melhores práticas do Python com exemplos simples que você pode aplicar instantaneamente para escrever um código mais bonito + Pythonico.

Instalando o Redis da origem

Como meu tataravô disse, nada cria garra como instalar a partir da fonte. Esta seção o guiará pelo download, criação e instalação do Redis. Prometo que isso não vai doer nem um pouco!

Observação :Esta seção é orientada para a instalação no Mac OS X ou Linux. Se você estiver usando o Windows, há um fork do Redis da Microsoft que pode ser instalado como um serviço do Windows. Basta dizer que o Redis como um programa vive mais confortavelmente em uma caixa Linux e que a configuração e o uso no Windows podem ser meticulosos.

Primeiro, baixe o código-fonte do Redis como um tarball:

$ redisurl="https://download.redis.io/redis-stable.tar.gz"

$ curl -s -o redis-stable.tar.gz $redisurl

Em seguida, mude para

root e extraia o código-fonte do arquivo para /usr/local/lib/ :$ sudo su root

$ mkdir -p /usr/local/lib/

$ chmod a+w /usr/local/lib/

$ tar -C /usr/local/lib/ -xzf redis-stable.tar.gz

Opcionalmente, agora você pode remover o próprio arquivo:

$ rm redis-stable.tar.gz

Isso deixará você com um repositório de código-fonte em

/usr/local/lib/redis-stable/ . Redis é escrito em C, então você precisará compilar, vincular e instalar com o make Utilitário:$ cd /usr/local/lib/redis-stable/

$ make && make install

Usando

make install faz duas ações:-

O primeiromakeO comando compila e vincula o código-fonte.

-

Omake installparte pega os binários e os copia para/usr/local/bin/para que você possa executá-los de qualquer lugar (assumindo que/usr/local/bin/está emPATH).

Aqui estão todos os passos até agora:

$ redisurl="https://download.redis.io/redis-stable.tar.gz"

$ curl -s -o redis-stable.tar.gz $redisurl

$ sudo su root

$ mkdir -p /usr/local/lib/

$ chmod a+w /usr/local/lib/

$ tar -C /usr/local/lib/ -xzf redis-stable.tar.gz

$ rm redis-stable.tar.gz

$ cd /usr/local/lib/redis-stable/

$ make && make install

Neste ponto, reserve um momento para confirmar se o Redis está em seu

PATH e verifique sua versão:$ redis-cli --version

redis-cli 5.0.3

Se seu shell não encontrar

redis-cli , verifique se /usr/local/bin/ está em seu PATH variável de ambiente e adicione-a se não. Além de

redis-cli , make install na verdade, leva a um punhado de arquivos executáveis diferentes (e um link simbólico) sendo colocados em /usr/local/bin/ :$ # A snapshot of executables that come bundled with Redis

$ ls -hFG /usr/local/bin/redis-* | sort

/usr/local/bin/redis-benchmark*

/usr/local/bin/redis-check-aof*

/usr/local/bin/redis-check-rdb*

/usr/local/bin/redis-cli*

/usr/local/bin/redis-sentinel@

/usr/local/bin/redis-server*

Embora todos eles tenham algum uso pretendido, os dois com os quais você provavelmente mais se importará são

redis-cli e redis-server , que descreveremos em breve. Mas antes de chegarmos a isso, é necessário definir alguma configuração de linha de base. Configurando o Redis

O Redis é altamente configurável. Embora ele funcione bem, vamos reservar um minuto para definir algumas opções de configuração básicas relacionadas à persistência do banco de dados e segurança básica:

$ sudo su root

$ mkdir -p /etc/redis/

$ touch /etc/redis/6379.conf

Agora, escreva o seguinte em

/etc/redis/6379.conf . Abordaremos o que a maioria deles significa gradualmente ao longo do tutorial:# /etc/redis/6379.conf

port 6379

daemonize yes

save 60 1

bind 127.0.0.1

tcp-keepalive 300

dbfilename dump.rdb

dir ./

rdbcompression yes

A configuração do Redis é autodocumentada, com o exemplo

redis.conf arquivo localizado na fonte do Redis para seu prazer de leitura. Se você estiver usando o Redis em um sistema de produção, vale a pena bloquear todas as distrações e reservar um tempo para ler este arquivo de amostra na íntegra para se familiarizar com os detalhes do Redis e ajustar sua configuração. Alguns tutoriais, incluindo partes da documentação do Redis, também podem sugerir a execução do script Shell

install_server.sh localizado em redis/utils/install_server.sh . Você é bem-vindo para executá-lo como uma alternativa mais abrangente para o acima, mas observe alguns pontos mais sutis sobre install_server.sh :- Não funcionará no Mac OS X, apenas no Debian e Ubuntu Linux.

- Ele injetará um conjunto mais completo de opções de configuração em

/etc/redis/6379.conf. - Ele escreverá um

initdo System V script para/etc/init.d/redis_6379que permitirá que você façasudo service redis_6379 start.

O guia de início rápido do Redis também contém uma seção sobre uma configuração mais adequada do Redis, mas as opções de configuração acima devem ser totalmente suficientes para este tutorial e introdução.

Observação de segurança: Alguns anos atrás, o autor do Redis apontou vulnerabilidades de segurança em versões anteriores do Redis se nenhuma configuração fosse definida. O Redis 3.2 (a versão atual 5.0.3 em março de 2019) fez etapas para evitar essa invasão, definindo o

protected-mode opção para yes por padrão. Definimos explicitamente

bind 127.0.0.1 para permitir que o Redis escute conexões apenas da interface localhost, embora você precise expandir essa lista branca em um servidor de produção real. O ponto de protected-mode é como uma proteção que imitará esse comportamento de vinculação ao localhost se você não especificar nada sob o bind opção. Com isso resolvido, agora podemos nos aprofundar no uso do próprio Redis.

Dez ou mais minutos para Redis

Esta seção fornecerá conhecimento suficiente do Redis para ser perigoso, descrevendo seu design e uso básico.

Primeiros passos

O Redis tem uma arquitetura cliente-servidor e usa um modelo de solicitação-resposta . Isso significa que você (o cliente) se conecta a um servidor Redis por meio de uma conexão TCP, na porta 6379 por padrão. Você solicita alguma ação (como alguma forma de leitura, escrita, obtenção, configuração ou atualização), e o servidor serve você de volta uma resposta.

Pode haver muitos clientes conversando com o mesmo servidor, o que é realmente o Redis ou qualquer aplicativo cliente-servidor. Cada cliente faz uma leitura (normalmente de bloqueio) em um soquete aguardando a resposta do servidor.

O

cli em redis-cli significa interface de linha de comando , e o server em redis-server é para, bem, executar um servidor. Da mesma forma que você executaria python na linha de comando, você pode executar redis-cli para saltar para um REPL interativo (Read Eval Print Loop) onde você pode executar comandos do cliente diretamente do shell. Primeiro, no entanto, você precisará iniciar o

redis-server para que você tenha um servidor Redis em execução para conversar. Uma maneira comum de fazer isso em desenvolvimento é iniciar um servidor no host local (endereço IPv4 127.0.0.1 ), que é o padrão, a menos que você informe ao Redis o contrário. Você também pode passar redis-server o nome do seu arquivo de configuração, que é semelhante a especificar todos os seus pares chave-valor como argumentos de linha de comando:$ redis-server /etc/redis/6379.conf

31829:C 07 Mar 2019 08:45:04.030 # oO0OoO0OoO0Oo Redis is starting oO0OoO0OoO0Oo

31829:C 07 Mar 2019 08:45:04.030 # Redis version=5.0.3, bits=64, commit=00000000, modified=0, pid=31829, just started

31829:C 07 Mar 2019 08:45:04.030 # Configuration loaded

Definimos o

daemonize opção de configuração para yes , para que o servidor seja executado em segundo plano. (Caso contrário, use --daemonize yes como uma opção para redis-server .) Agora você está pronto para iniciar o Redis REPL. Digite

redis-cli na sua linha de comando. Você verá o host:port do servidor par seguido por um > incitar:127.0.0.1:6379>

Aqui está um dos comandos mais simples do Redis,

PING , que apenas testa a conectividade com o servidor e retorna "PONG" se as coisas estão bem:127.0.0.1:6379> PING

PONG

Os comandos do Redis não diferenciam maiúsculas de minúsculas, embora seus equivalentes em Python definitivamente não sejam.

Observação: Como outra verificação de integridade, você pode pesquisar o ID do processo do servidor Redis com

pgrep :$ pgrep redis-server

26983

Para matar o servidor, use

pkill redis-server da linha de comando. No Mac OS X, você também pode usar redis-cli shutdown . Em seguida, usaremos alguns dos comandos comuns do Redis e os compararemos com a aparência deles em Python puro.

Redis como um dicionário Python

Redis significa Serviço de Dicionário Remoto .

“Você quer dizer, como um dicionário Python?” você pode perguntar.

Sim. De um modo geral, existem muitos paralelos que você pode traçar entre um dicionário Python (ou tabela de hash genérica) e o que o Redis é e faz:

-

Um banco de dados Redis contém key:value pares e suporta comandos comoGET,SETeDEL, bem como várias centenas de comandos adicionais.

-

Redis chaves são sempre cordas.

-

Redis valores podem ser vários tipos de dados diferentes. Abordaremos alguns dos tipos de dados de valor mais essenciais neste tutorial:string,list,hashes, esets. Alguns tipos avançados incluem itens geoespaciais e o novo tipo de fluxo.

-

Muitos comandos Redis operam em tempo O(1) constante, assim como recuperar um valor de um Pythondictou qualquer tabela de hash.

O criador do Redis, Salvatore Sanfilippo, provavelmente não adoraria a comparação de um banco de dados Redis com um Python simples

dict . Ele chama o projeto de “servidor de estrutura de dados” (em vez de um armazenamento de valor-chave, como memcached) porque, para seu crédito, o Redis suporta o armazenamento de tipos adicionais de chave:valor tipos de dados além de string:string . Mas para nossos propósitos aqui, é uma comparação útil se você estiver familiarizado com o objeto de dicionário do Python. Vamos pular e aprender pelo exemplo. Nosso primeiro banco de dados de brinquedos (com ID 0) será um mapeamento de país:cidade capital , onde usamos

SET para definir pares de valores-chave:127.0.0.1:6379> SET Bahamas Nassau

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> SET Croatia Zagreb

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> GET Croatia

"Zagreb"

127.0.0.1:6379> GET Japan

(nil)

A sequência correspondente de instruções em Python puro ficaria assim:

>>>

>>> capitals = {}

>>> capitals["Bahamas"] = "Nassau"

>>> capitals["Croatia"] = "Zagreb"

>>> capitals.get("Croatia")

'Zagreb'

>>> capitals.get("Japan") # None

Usamos

capitals.get("Japan") em vez de capitals["Japan"] porque o Redis retornará nil em vez de um erro quando uma chave não é encontrada, o que é análogo ao None do Python . O Redis também permite definir e obter vários pares de valores-chave em um comando,

MSET e MGET , respectivamente:127.0.0.1:6379> MSET Lebanon Beirut Norway Oslo France Paris

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> MGET Lebanon Norway Bahamas

1) "Beirut"

2) "Oslo"

3) "Nassau"

A coisa mais próxima em Python é com

dict.update() :>>>

>>> capitals.update({

... "Lebanon": "Beirut",

... "Norway": "Oslo",

... "France": "Paris",

... })

>>> [capitals.get(k) for k in ("Lebanon", "Norway", "Bahamas")]

['Beirut', 'Oslo', 'Nassau']

Usamos

.get() em vez de .__getitem__() para imitar o comportamento do Redis de retornar um valor semelhante a nulo quando nenhuma chave for encontrada. Como terceiro exemplo, o

EXISTS command faz o que parece, que é verificar se existe uma chave:127.0.0.1:6379> EXISTS Norway

(integer) 1

127.0.0.1:6379> EXISTS Sweden

(integer) 0

Python tem o

in palavra-chave para testar a mesma coisa, que roteia para dict.__contains__(key) :>>>

>>> "Norway" in capitals

True

>>> "Sweden" in capitals

False

Esses poucos exemplos destinam-se a mostrar, usando Python nativo, o que está acontecendo em alto nível com alguns comandos comuns do Redis. Não há componente cliente-servidor aqui para os exemplos do Python e

redis-py ainda não entrou em cena. Isso serve apenas para mostrar a funcionalidade do Redis por exemplo. Aqui está um resumo dos poucos comandos Redis que você viu e seus equivalentes funcionais em Python:

capitals["Bahamas"] = "Nassau"

capitals.get("Croatia")

capitals.update(

{

"Lebanon": "Beirut",

"Norway": "Oslo",

"France": "Paris",

}

)

[capitals[k] for k in ("Lebanon", "Norway", "Bahamas")]

"Norway" in capitals

A biblioteca cliente Python Redis,

redis-py , que você abordará em breve neste artigo, faz as coisas de maneira diferente. Ele encapsula uma conexão TCP real para um servidor Redis e envia comandos brutos, como bytes serializados usando o REdis Serialization Protocol (RESP), para o servidor. Em seguida, ele pega a resposta bruta e a analisa de volta em um objeto Python, como bytes , int , ou mesmo datetime.datetime . Observação :até agora, você conversou com o servidor Redis por meio do

redis-cli interativo REPL. Você também pode emitir comandos diretamente, da mesma forma que passaria o nome de um script para o python executável, como python myscript.py . Até agora, você viu alguns dos tipos de dados fundamentais do Redis, que são um mapeamento de string:string . Embora esse par de valores-chave seja comum na maioria dos armazenamentos de valores-chave, o Redis oferece vários outros tipos de valores possíveis, que você verá a seguir.

Mais tipos de dados em Python vs Redis

Antes de iniciar o

redis-py Cliente Python, também ajuda a ter uma compreensão básica de mais alguns tipos de dados do Redis. Para ser claro, todas as chaves do Redis são strings. É o valor que pode assumir tipos de dados (ou estruturas) além dos valores de string usados nos exemplos até agora. Um hash é um mapeamento de string:string , chamado valor do campo pares, que fica sob uma chave de nível superior:

127.0.0.1:6379> HSET realpython url "https://realpython.com/"

(integer) 1

127.0.0.1:6379> HSET realpython github realpython

(integer) 1

127.0.0.1:6379> HSET realpython fullname "Real Python"

(integer) 1

Isso define três pares de valor de campo para uma chave ,

"realpython" . Se você está acostumado com a terminologia e os objetos do Python, isso pode ser confuso. Um hash Redis é aproximadamente análogo a um Python dict que está aninhado em um nível de profundidade:data = {

"realpython": {

"url": "https://realpython.com/",

"github": "realpython",

"fullname": "Real Python",

}

}

Os campos do Redis são semelhantes às chaves Python de cada par chave-valor aninhado no dicionário interno acima. O Redis reserva o termo chave para a chave de banco de dados de nível superior que contém a própria estrutura de hash.

Assim como há

MSET para string:string básico pares chave-valor, há também HMSET para hashes para definir vários pares dentro o objeto de valor de hash:127.0.0.1:6379> HMSET pypa url "https://www.pypa.io/" github pypa fullname "Python Packaging Authority"

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> HGETALL pypa

1) "url"

2) "https://www.pypa.io/"

3) "github"

4) "pypa"

5) "fullname"

6) "Python Packaging Authority"

Usando

HMSET é provavelmente um paralelo mais próximo da maneira como atribuímos data para um dicionário aninhado acima, em vez de definir cada par aninhado como é feito com HSET . Dois tipos de valor adicionais são listas e conjuntos , que pode substituir um hash ou string como um valor Redis. Eles são em grande parte o que parecem, então não vou tomar seu tempo com exemplos adicionais. Hashes, listas e conjuntos têm alguns comandos que são específicos para esse tipo de dado, que em alguns casos são indicados por sua letra inicial:

-

Hashes: Os comandos para operar em hashes começam com umH, comoHSET,HGET, ouHMSET.

-

Conjuntos: Os comandos para operar em conjuntos começam com umS, comoSCARD, que obtém o número de elementos no valor definido correspondente a uma determinada chave.

-

Listas: Os comandos para operar em listas começam com umLouR. Os exemplos incluemLPOPeRPUSH. OLouRrefere-se a qual lado da lista é operado. Alguns comandos de lista também são precedidos por umB, que significa bloqueio . Uma operação de bloqueio não permite que outras operações a interrompam durante a execução. Por exemplo,BLPOPexecuta um pop esquerdo de bloqueio em uma estrutura de lista.

Observação: Uma característica notável do tipo de lista do Redis é que é uma lista vinculada em vez de uma matriz. Isso significa que anexar é O(1) enquanto indexar em um número de índice arbitrário é O(N).

Aqui está uma lista rápida de comandos que são específicos para os tipos de dados string, hash, list e set no Redis:

| Tipo | Comandos |

|---|---|

| Conjuntos | SADD , SCARD , SDIFF , SDIFFSTORE , SINTER , SINTERSTORE , SISMEMBER , SMEMBERS , SMOVE , SPOP , SRANDMEMBER , SREM , SSCAN , SUNION , SUNIONSTORE |

| Hashes | HDEL , HEXISTS , HGET , HGETALL , HINCRBY , HINCRBYFLOAT , HKEYS , HLEN , HMGET , HMSET , HSCAN , HSET , HSETNX , HSTRLEN , HVALS |

| Listas | BLPOP , BRPOP , BRPOPLPUSH , LINDEX , LINSERT , LLEN , LPOP , LPUSH , LPUSHX , LRANGE , LREM , LSET , LTRIM , RPOP , RPOPLPUSH , RPUSH , RPUSHX |

| Cordas | APPEND , BITCOUNT , BITFIELD , BITOP , BITPOS , DECR , DECRBY , GET , GETBIT , GETRANGE , GETSET , INCR , INCRBY , INCRBYFLOAT , MGET , MSET , MSETNX , PSETEX , SET , SETBIT , SETEX , SETNX , SETRANGE , STRLEN |

Esta tabela não é uma imagem completa dos comandos e tipos do Redis. Há uma variedade de tipos de dados mais avançados, como itens geoespaciais, conjuntos classificados e HyperLogLog. Na página de comandos do Redis, você pode filtrar por grupo de estrutura de dados. Há também o resumo dos tipos de dados e a introdução aos tipos de dados do Redis.

Como vamos passar a fazer coisas em Python, agora você pode limpar seu banco de dados de brinquedos com

FLUSHDB e saia do redis-cli REPL:127.0.0.1:6379> FLUSHDB

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> QUIT

Isso o levará de volta ao prompt do shell. Você pode sair do

redis-server rodando em segundo plano, já que você também precisará dele para o resto do tutorial. Usando redis-py :Redis em Python

Agora que você já domina alguns conceitos básicos do Redis, é hora de pular para o

redis-py , o cliente Python que permite que você converse com o Redis a partir de uma API Python amigável. Primeiros passos

redis-py é uma biblioteca cliente Python bem estabelecida que permite que você converse com um servidor Redis diretamente por meio de chamadas Python:$ python -m pip install redis

Em seguida, verifique se o servidor Redis ainda está funcionando em segundo plano. Você pode verificar com

pgrep redis-server , e se você chegar de mãos vazias, reinicie um servidor local com redis-server /etc/redis/6379.conf . Agora, vamos entrar na parte centrada em Python das coisas. Aqui está o "hello world" de

redis-py :>>>

1>>> import redis

2>>> r = redis.Redis()

3>>> r.mset({"Croatia": "Zagreb", "Bahamas": "Nassau"})

4True

5>>> r.get("Bahamas")

6b'Nassau'

Redis , usado na Linha 2, é a classe central do pacote e o cavalo de batalha pelo qual você executa (quase) qualquer comando Redis. A conexão e a reutilização do soquete TCP são feitas para você nos bastidores, e você chama os comandos do Redis usando métodos na instância da classe r . Observe também que o tipo do objeto retornado,

b'Nassau' na linha 6, são os bytes do Python tipo, não str . São bytes em vez de str esse é o tipo de retorno mais comum em redis-py , então você pode precisar chamar r.get("Bahamas").decode("utf-8") dependendo do que você quer realmente fazer com o bytestring retornado. O código acima parece familiar? Os métodos em quase todos os casos correspondem ao nome do comando Redis que faz a mesma coisa. Aqui, você chamou

r.mset() e r.get() , que correspondem a MSET e GET na API nativa do Redis. Isso também significa que

HGETALL torna-se r.hgetall() , PING torna-se r.ping() , e assim por diante. Existem algumas exceções, mas a regra vale para a grande maioria dos comandos. Embora os argumentos do comando Redis geralmente se traduzam em uma assinatura de método de aparência semelhante, eles usam objetos Python. Por exemplo, a chamada para

r.mset() no exemplo acima usa um Python dict como seu primeiro argumento, em vez de uma sequência de bytestrings. Criamos o

Redis instância r sem argumentos, mas vem com vários parâmetros, se você precisar deles:# From redis/client.py

class Redis(object):

def __init__(self, host='localhost', port=6379,

db=0, password=None, socket_timeout=None,

# ...

Você pode ver que o padrão hostname:port par é

localhost:6379 , que é exatamente o que precisamos no caso de nosso redis-server mantido localmente instância. O

db parâmetro é o número do banco de dados. Você pode gerenciar vários bancos de dados no Redis de uma só vez, e cada um é identificado por um número inteiro. O número máximo de bancos de dados é 16 por padrão. Quando você executa apenas

redis-cli a partir da linha de comando, isso inicia você no banco de dados 0. Use o -n sinalizador para iniciar um novo banco de dados, como em redis-cli -n 5 . Tipos de chave permitidos

Uma coisa que vale a pena saber é que

redis-py requer que você passe chaves que são bytes , str , int , ou float . (Irá converter os últimos 3 desses tipos para bytes antes de enviá-los para o servidor.) Considere um caso em que você deseja usar datas do calendário como chaves:

>>>

>>> import datetime

>>> today = datetime.date.today()

>>> visitors = {"dan", "jon", "alex"}

>>> r.sadd(today, *visitors)

Traceback (most recent call last):

# ...

redis.exceptions.DataError: Invalid input of type: 'date'.

Convert to a byte, string or number first.

Você precisará converter explicitamente o Python

date objeto para str , que você pode fazer com .isoformat() :>>>

>>> stoday = today.isoformat() # Python 3.7+, or use str(today)

>>> stoday

'2019-03-10'

>>> r.sadd(stoday, *visitors) # sadd: set-add

3

>>> r.smembers(stoday)

{b'dan', b'alex', b'jon'}

>>> r.scard(today.isoformat())

3

Para recapitular, o próprio Redis só permite strings como chaves.

redis-py é um pouco mais liberal em quais tipos de Python ele aceitará, embora no final converta tudo em bytes antes de enviá-los para um servidor Redis. Exemplo:PyHats.com

É hora de dar um exemplo mais completo. Vamos fingir que decidimos começar um site lucrativo, PyHats.com, que vende chapéus escandalosamente caros para quem os comprar, e contratamos você para construir o site.

Você usará o Redis para lidar com parte do catálogo de produtos, inventário e detecção de tráfego de bot para PyHats.com.

É o primeiro dia do site e vamos vender três chapéus de edição limitada. Cada hat é mantido em um hash Redis de pares de valor de campo, e o hash tem uma chave que é um número inteiro aleatório prefixado, como

hat:56854717 . Usando o hat: prefix é a convenção do Redis para criar um tipo de namespace em um banco de dados Redis:import random

random.seed(444)

hats = {f"hat:{random.getrandbits(32)}": i for i in (

{

"color": "black",

"price": 49.99,

"style": "fitted",

"quantity": 1000,

"npurchased": 0,

},

{

"color": "maroon",

"price": 59.99,

"style": "hipster",

"quantity": 500,

"npurchased": 0,

},

{

"color": "green",

"price": 99.99,

"style": "baseball",

"quantity": 200,

"npurchased": 0,

})

}

Vamos começar com o banco de dados

1 já que usamos o banco de dados 0 em um exemplo anterior:>>>

>>> r = redis.Redis(db=1)

Para fazer uma gravação inicial desses dados no Redis, podemos usar

.hmset() (hash multi-set), chamando-o para cada dicionário. O “multi” é uma referência à configuração de vários pares de valor de campo, onde “campo” neste caso corresponde a uma chave de qualquer um dos dicionários aninhados em hats : 1>>> with r.pipeline() as pipe:

2... for h_id, hat in hats.items():

3... pipe.hmset(h_id, hat)

4... pipe.execute()

5Pipeline<ConnectionPool<Connection<host=localhost,port=6379,db=1>>>

6Pipeline<ConnectionPool<Connection<host=localhost,port=6379,db=1>>>

7Pipeline<ConnectionPool<Connection<host=localhost,port=6379,db=1>>>

8[True, True, True]

9

10>>> r.bgsave()

11True

O bloco de código acima também apresenta o conceito de pipelining do Redis , que é uma maneira de reduzir o número de transações de ida e volta necessárias para gravar ou ler dados do servidor Redis. Se você tivesse acabado de chamar

r.hmset() três vezes, isso exigiria uma operação de ida e volta para cada linha escrita. Com um pipeline, todos os comandos são armazenados em buffer no lado do cliente e enviados de uma só vez, de uma só vez, usando

pipe.hmset() na Linha 3. É por isso que os três True as respostas são todas retornadas de uma vez, quando você chama pipe.execute() na Linha 4. Você verá um caso de uso mais avançado para um pipeline em breve. Observação :Os documentos do Redis fornecem um exemplo de como fazer a mesma coisa com o

redis-cli , onde você pode canalizar o conteúdo de um arquivo local para fazer a inserção em massa. Vamos verificar rapidamente se tudo está lá em nosso banco de dados Redis:

>>>

>>> pprint(r.hgetall("hat:56854717"))

{b'color': b'green',

b'npurchased': b'0',

b'price': b'99.99',

b'quantity': b'200',

b'style': b'baseball'}

>>> r.keys() # Careful on a big DB. keys() is O(N)

[b'56854717', b'1236154736', b'1326692461']

A primeira coisa que queremos simular é o que acontece quando um usuário clica em Comprar . Se o item estiver em estoque, aumente seu

npurchased por 1 e diminuir sua quantity (inventário) por 1. Você pode usar .hincrby() para fazer isso:>>>

>>> r.hincrby("hat:56854717", "quantity", -1)

199

>>> r.hget("hat:56854717", "quantity")

b'199'

>>> r.hincrby("hat:56854717", "npurchased", 1)

1

Observação :

HINCRBY ainda opera em um valor de hash que é uma string, mas tenta interpretar a string como um inteiro assinado de 64 bits de base 10 para executar a operação. Isso se aplica a outros comandos relacionados ao incremento e decremento para outras estruturas de dados, como

INCR , INCRBY , INCRBYFLOAT , ZINCRBY e HINCRBYFLOAT . Você receberá um erro se a string no valor não puder ser representada como um inteiro. Não é realmente tão simples, no entanto. Alterando a

quantity e npurchased em duas linhas de código esconde a realidade de que um clique, uma compra e um pagamento envolvem mais do que isso. Precisamos fazer mais algumas verificações para garantir que não deixamos alguém com uma carteira mais leve e sem chapéu:- Etapa 1: Verifique se o item está em estoque ou abra uma exceção no back-end.

- Etapa 2: Se estiver em estoque, execute a transação, diminua a

quantitycampo e aumente onpurchasedcampo. - Etapa 3: Be alert for any changes that alter the inventory in between the first two steps (a race condition).

Step 1 is relatively straightforward:it consists of an

.hget() to check the available quantity. Step 2 is a little bit more involved. The pair of increase and decrease operations need to be executed atomically :either both should be completed successfully, or neither should be (in the case that at least one fails).

With client-server frameworks, it’s always crucial to pay attention to atomicity and look out for what could go wrong in instances where multiple clients are trying to talk to the server at once. The answer to this in Redis is to use a transaction block, meaning that either both or neither of the commands get through.

In

redis-py , Pipeline is a transactional pipeline class by default. This means that, even though the class is actually named for something else (pipelining), it can be used to create a transaction block also. In Redis, a transaction starts with

MULTI and ends with EXEC : 1127.0.0.1:6379> MULTI

2127.0.0.1:6379> HINCRBY 56854717 quantity -1

3127.0.0.1:6379> HINCRBY 56854717 npurchased 1

4127.0.0.1:6379> EXEC

MULTI (Line 1) marks the start of the transaction, and EXEC (Line 4) marks the end. Everything in between is executed as one all-or-nothing buffered sequence of commands. This means that it will be impossible to decrement quantity (Line 2) but then have the balancing npurchased increment operation fail (Line 3). Let’s circle back to Step 3:we need to be aware of any changes that alter the inventory in between the first two steps.

Step 3 is the trickiest. Let’s say that there is one lone hat remaining in our inventory. In between the time that User A checks the quantity of hats remaining and actually processes their transaction, User B also checks the inventory and finds likewise that there is one hat listed in stock. Both users will be allowed to purchase the hat, but we have 1 hat to sell, not 2, so we’re on the hook and one user is out of their money. Not good.

Redis has a clever answer for the dilemma in Step 3:it’s called optimistic locking , and is different than how typical locking works in an RDBMS such as PostgreSQL. Optimistic locking, in a nutshell, means that the calling function (client) does not acquire a lock, but rather monitors for changes in the data it is writing to during the time it would have held a lock . If there’s a conflict during that time, the calling function simply tries the whole process again.

You can effect optimistic locking by using the

WATCH command (.watch() in redis-py ), which provides a check-and-set behavior. Let’s introduce a big chunk of code and walk through it afterwards step by step. You can picture

buyitem() as being called any time a user clicks on a Buy Now or Purchase botão. Its purpose is to confirm the item is in stock and take an action based on that result, all in a safe manner that looks out for race conditions and retries if one is detected: 1import logging

2import redis

3

4logging.basicConfig()

5

6class OutOfStockError(Exception):

7 """Raised when PyHats.com is all out of today's hottest hat"""

8

9def buyitem(r: redis.Redis, itemid: int) -> None:

10 with r.pipeline() as pipe:

11 error_count = 0

12 while True:

13 try:

14 # Get available inventory, watching for changes

15 # related to this itemid before the transaction

16 pipe.watch(itemid)

17 nleft: bytes = r.hget(itemid, "quantity")

18 if nleft > b"0":

19 pipe.multi()

20 pipe.hincrby(itemid, "quantity", -1)

21 pipe.hincrby(itemid, "npurchased", 1)

22 pipe.execute()

23 break

24 else:

25 # Stop watching the itemid and raise to break out

26 pipe.unwatch()

27 raise OutOfStockError(

28 f"Sorry, {itemid} is out of stock!"

29 )

30 except redis.WatchError:

31 # Log total num. of errors by this user to buy this item,

32 # then try the same process again of WATCH/HGET/MULTI/EXEC

33 error_count += 1

34 logging.warning(

35 "WatchError #%d: %s; retrying",

36 error_count, itemid

37 )

38 return None

The critical line occurs at Line 16 with

pipe.watch(itemid) , which tells Redis to monitor the given itemid for any changes to its value. The program checks the inventory through the call to r.hget(itemid, "quantity") , in Line 17:16pipe.watch(itemid)

17nleft: bytes = r.hget(itemid, "quantity")

18if nleft > b"0":

19 # Item in stock. Proceed with transaction.

If the inventory gets touched during this short window between when the user checks the item stock and tries to purchase it, then Redis will return an error, and

redis-py will raise a WatchError (Line 30). That is, if any of the hash pointed to by itemid changes after the .hget() call but before the subsequent .hincrby() calls in Lines 20 and 21, then we’ll re-run the whole process in another iteration of the while True loop as a result. This is the “optimistic” part of the locking:rather than letting the client have a time-consuming total lock on the database through the getting and setting operations, we leave it up to Redis to notify the client and user only in the case that calls for a retry of the inventory check.

One key here is in understanding the difference between client-side and server-side operations:

nleft = r.hget(itemid, "quantity")

This Python assignment brings the result of

r.hget() client-side. Conversely, methods that you call on pipe effectively buffer all of the commands into one, and then send them to the server in a single request:16pipe.multi()

17pipe.hincrby(itemid, "quantity", -1)

18pipe.hincrby(itemid, "npurchased", 1)

19pipe.execute()

No data comes back to the client side in the middle of the transactional pipeline. You need to call

.execute() (Line 19) to get the sequence of results back all at once. Even though this block contains two commands, it consists of exactly one round-trip operation from client to server and back.

This means that the client can’t immediately use the result of

pipe.hincrby(itemid, "quantity", -1) , from Line 20, because methods on a Pipeline return just the pipe instance itself. We haven’t asked anything from the server at this point. While normally .hincrby() returns the resulting value, you can’t immediately reference it on the client side until the entire transaction is completed. There’s a catch-22:this is also why you can’t put the call to

.hget() into the transaction block. If you did this, then you’d be unable to know if you want to increment the npurchased field yet, since you can’t get real-time results from commands that are inserted into a transactional pipeline. Finally, if the inventory sits at zero, then we

UNWATCH the item ID and raise an OutOfStockError (Line 27), ultimately displaying that coveted Sold Out page that will make our hat buyers desperately want to buy even more of our hats at ever more outlandish prices:24else:

25 # Stop watching the itemid and raise to break out

26 pipe.unwatch()

27 raise OutOfStockError(

28 f"Sorry, {itemid} is out of stock!"

29 )

Here’s an illustration. Keep in mind that our starting quantity is

199 for hat 56854717 since we called .hincrby() above. Let’s mimic 3 purchases, which should modify the quantity and npurchased Campos:>>>

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> r.hmget("hat:56854717", "quantity", "npurchased") # Hash multi-get

[b'196', b'4']

Now, we can fast-forward through more purchases, mimicking a stream of purchases until the stock depletes to zero. Again, picture these coming from a whole bunch of different clients rather than just one

Redis instance:>>>

>>> # Buy remaining 196 hats for item 56854717 and deplete stock to 0

>>> for _ in range(196):

... buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> r.hmget("hat:56854717", "quantity", "npurchased")

[b'0', b'200']

Now, when some poor user is late to the game, they should be met with an

OutOfStockError that tells our application to render an error message page on the frontend:>>>

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 20, in buyitem

__main__.OutOfStockError: Sorry, hat:56854717 is out of stock!

Looks like it’s time to restock.

Using Key Expiry

Let’s introduce key expiry , which is another distinguishing feature in Redis. When you expire a key, that key and its corresponding value will be automatically deleted from the database after a certain number of seconds or at a certain timestamp.

In

redis-py , one way that you can accomplish this is through .setex() , which lets you set a basic string:string key-value pair with an expiration:>>>

1>>> from datetime import timedelta

2

3>>> # setex: "SET" with expiration

4>>> r.setex(

5... "runner",

6... timedelta(minutes=1),

7... value="now you see me, now you don't"

8... )

9True

You can specify the second argument as a number in seconds or a

timedelta object, as in Line 6 above. I like the latter because it seems less ambiguous and more deliberate. There are also methods (and corresponding Redis commands, of course) to get the remaining lifetime (time-to-live ) of a key that you’ve set to expire:

>>>

>>> r.ttl("runner") # "Time To Live", in seconds

58

>>> r.pttl("runner") # Like ttl, but milliseconds

54368

Below, you can accelerate the window until expiration, and then watch the key expire, after which

r.get() will return None and .exists() will return 0 :>>>

>>> r.get("runner") # Not expired yet

b"now you see me, now you don't"

>>> r.expire("runner", timedelta(seconds=3)) # Set new expire window

True

>>> # Pause for a few seconds

>>> r.get("runner")

>>> r.exists("runner") # Key & value are both gone (expired)

0

The table below summarizes commands related to key-value expiration, including the ones covered above. The explanations are taken directly from

redis-py method docstrings:| Signature | Purpose |

|---|---|

r.setex(name, time, value) | Sets the value of key name to value that expires in time seconds, where time can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.psetex(name, time_ms, value) | Sets the value of key name to value that expires in time_ms milliseconds, where time_ms can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.expire(name, time) | Sets an expire flag on key name for time seconds, where time can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.expireat(name, when) | Sets an expire flag on key name , where when can be represented as an int indicating Unix time or a Python datetime object |

r.persist(name) | Removes an expiration on name |

r.pexpire(name, time) | Sets an expire flag on key name for time milliseconds, and time can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.pexpireat(name, when) | Sets an expire flag on key name , where when can be represented as an int representing Unix time in milliseconds (Unix time * 1000) or a Python datetime object |

r.pttl(name) | Returns the number of milliseconds until the key name will expire |

r.ttl(name) | Returns the number of seconds until the key name will expire |

PyHats.com, Part 2

A few days after its debut, PyHats.com has attracted so much hype that some enterprising users are creating bots to buy hundreds of items within seconds, which you’ve decided isn’t good for the long-term health of your hat business.

Now that you’ve seen how to expire keys, let’s put it to use on the backend of PyHats.com.

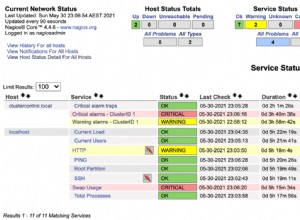

We’re going to create a new Redis client that acts as a consumer (or watcher) and processes a stream of incoming IP addresses, which in turn may come from multiple HTTPS connections to the website’s server.

The watcher’s goal is to monitor a stream of IP addresses from multiple sources, keeping an eye out for a flood of requests from a single address within a suspiciously short amount of time.

Some middleware on the website server pushes all incoming IP addresses into a Redis list with

.lpush() . Here’s a crude way of mimicking some incoming IPs, using a fresh Redis database:>>>

>>> r = redis.Redis(db=5)

>>> r.lpush("ips", "51.218.112.236")

1

>>> r.lpush("ips", "90.213.45.98")

2

>>> r.lpush("ips", "115.215.230.176")

3

>>> r.lpush("ips", "51.218.112.236")

4

As you can see,

.lpush() returns the length of the list after the push operation succeeds. Each call of .lpush() puts the IP at the beginning of the Redis list that is keyed by the string "ips" . In this simplified simulation, the requests are all technically from the same client, but you can think of them as potentially coming from many different clients and all being pushed to the same database on the same Redis server.

Now, open up a new shell tab or window and launch a new Python REPL. In this shell, you’ll create a new client that serves a very different purpose than the rest, which sits in an endless

while True loop and does a blocking left-pop BLPOP call on the ips list, processing each address: 1# New shell window or tab

2

3import datetime

4import ipaddress

5

6import redis

7

8# Where we put all the bad egg IP addresses

9blacklist = set()

10MAXVISITS = 15

11

12ipwatcher = redis.Redis(db=5)

13

14while True:

15 _, addr = ipwatcher.blpop("ips")

16 addr = ipaddress.ip_address(addr.decode("utf-8"))

17 now = datetime.datetime.utcnow()

18 addrts = f"{addr}:{now.minute}"

19 n = ipwatcher.incrby(addrts, 1)

20 if n >= MAXVISITS:

21 print(f"Hat bot detected!: {addr}")

22 blacklist.add(addr)

23 else:

24 print(f"{now}: saw {addr}")

25 _ = ipwatcher.expire(addrts, 60)

Let’s walk through a few important concepts.

The

ipwatcher acts like a consumer, sitting around and waiting for new IPs to be pushed on the "ips" Redis list. It receives them as bytes , such as b”51.218.112.236”, and makes them into a more proper address object with the ipaddress módulo:15_, addr = ipwatcher.blpop("ips")

16addr = ipaddress.ip_address(addr.decode("utf-8"))

Then you form a Redis string key using the address and minute of the hour at which the

ipwatcher saw the address, incrementing the corresponding count by 1 and getting the new count in the process:17now = datetime.datetime.utcnow()

18addrts = f"{addr}:{now.minute}"

19n = ipwatcher.incrby(addrts, 1)

If the address has been seen more than

MAXVISITS , then it looks as if we have a PyHats.com web scraper on our hands trying to create the next tulip bubble. Alas, we have no choice but to give this user back something like a dreaded 403 status code. We use

ipwatcher.expire(addrts, 60) to expire the (address minute) combination 60 seconds from when it was last seen. This is to prevent our database from becoming clogged up with stale one-time page viewers. If you execute this code block in a new shell, you should immediately see this output:

2019-03-11 15:10:41.489214: saw 51.218.112.236

2019-03-11 15:10:41.490298: saw 115.215.230.176

2019-03-11 15:10:41.490839: saw 90.213.45.98

2019-03-11 15:10:41.491387: saw 51.218.112.236

The output appears right away because those four IPs were sitting in the queue-like list keyed by

"ips" , waiting to be pulled out by our ipwatcher . Using .blpop() (or the BLPOP command) will block until an item is available in the list, then pops it off. It behaves like Python’s Queue.get() , which also blocks until an item is available. Besides just spitting out IP addresses, our

ipwatcher has a second job. For a given minute of an hour (minute 1 through minute 60), ipwatcher will classify an IP address as a hat-bot if it sends 15 or more GET requests in that minute. Switch back to your first shell and mimic a page scraper that blasts the site with 20 requests in a few milliseconds:

for _ in range(20):

r.lpush("ips", "104.174.118.18")

Finally, toggle back to the second shell holding

ipwatcher , and you should see an output like this:2019-03-11 15:15:43.041363: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.042027: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.042598: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.043143: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.043725: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.044244: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.044760: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.045288: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.045806: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.046318: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.046829: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.047392: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.047966: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.048479: saw 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Now, Ctrl +C out of the

while True loop and you’ll see that the offending IP has been added to your blacklist:>>>

>>> blacklist

{IPv4Address('104.174.118.18')}

Can you find the defect in this detection system? The filter checks the minute as

.minute rather than the last 60 seconds (a rolling minute). Implementing a rolling check to monitor how many times a user has been seen in the last 60 seconds would be trickier. There’s a crafty solution using using Redis’ sorted sets at ClassDojo. Josiah Carlson’s Redis in Action also presents a more elaborate and general-purpose example of this section using an IP-to-location cache table. Persistence and Snapshotting

One of the reasons that Redis is so fast in both read and write operations is that the database is held in memory (RAM) on the server. However, a Redis database can also be stored (persisted) to disk in a process called snapshotting. The point behind this is to keep a physical backup in binary format so that data can be reconstructed and put back into memory when needed, such as at server startup.

You already enabled snapshotting without knowing it when you set up basic configuration at the beginning of this tutorial with the

save opção:# /etc/redis/6379.conf

port 6379

daemonize yes

save 60 1

bind 127.0.0.1

tcp-keepalive 300

dbfilename dump.rdb

dir ./

rdbcompression yes

The format is

save <seconds> <changes> . This tells Redis to save the database to disk if both the given number of seconds and number of write operations against the database occurred. In this case, we’re telling Redis to save the database to disk every 60 seconds if at least one modifying write operation occurred in that 60-second timespan. This is a fairly aggressive setting versus the sample Redis config file, which uses these three save directives:# Default redis/redis.conf

save 900 1

save 300 10

save 60 10000

An RDB snapshot is a full (rather than incremental) point-in-time capture of the database. (RDB refers to a Redis Database File.) We also specified the directory and file name of the resulting data file that gets written:

# /etc/redis/6379.conf

port 6379

daemonize yes

save 60 1

bind 127.0.0.1

tcp-keepalive 300

dbfilename dump.rdb

dir ./

rdbcompression yes

This instructs Redis to save to a binary data file called

dump.rdb in the current working directory of wherever redis-server was executed from:$ file -b dump.rdb

data

You can also manually invoke a save with the Redis command

BGSAVE :127.0.0.1:6379> BGSAVE

Background saving started

The “BG” in

BGSAVE indicates that the save occurs in the background. This option is available in a redis-py method as well:>>>

>>> r.lastsave() # Redis command: LASTSAVE

datetime.datetime(2019, 3, 10, 21, 56, 50)

>>> r.bgsave()

True

>>> r.lastsave()

datetime.datetime(2019, 3, 10, 22, 4, 2)

This example introduces another new command and method,

.lastsave() . In Redis, it returns the Unix timestamp of the last DB save, which Python gives back to you as a datetime objeto. Above, you can see that the r.lastsave() result changes as a result of r.bgsave() . r.lastsave() will also change if you enable automatic snapshotting with the save configuration option. To rephrase all of this, there are two ways to enable snapshotting:

- Explicitly, through the Redis command

BGSAVEorredis-pymethod.bgsave() - Implicitly, through the

saveconfiguration option (which you can also set with.config_set()inredis-py)

RDB snapshotting is fast because the parent process uses the

fork() system call to pass off the time-intensive write to disk to a child process, so that the parent process can continue on its way. This is what the background in BGSAVE refers to. There’s also

SAVE (.save() in redis-py ), but this does a synchronous (blocking) save rather than using fork() , so you shouldn’t use it without a specific reason. Even though

.bgsave() occurs in the background, it’s not without its costs. The time for fork() itself to occur can actually be substantial if the Redis database is large enough in the first place. If this is a concern, or if you can’t afford to miss even a tiny slice of data lost due to the periodic nature of RDB snapshotting, then you should look into the append-only file (AOF) strategy that is an alternative to snapshotting. AOF copies Redis commands to disk in real time, allowing you to do a literal command-based reconstruction by replaying these commands.

Serialization Workarounds

Let’s get back to talking about Redis data structures. With its hash data structure, Redis in effect supports nesting one level deep:

127.0.0.1:6379> hset mykey field1 value1

The Python client equivalent would look like this:

r.hset("mykey", "field1", "value1")

Here, you can think of

"field1": "value1" as being the key-value pair of a Python dict, {"field1": "value1"} , while mykey is the top-level key:| Redis Command | Pure-Python Equivalent |

|---|---|

r.set("key", "value") | r = {"key": "value"} |

r.hset("key", "field", "value") | r = {"key": {"field": "value"}} |

But what if you want the value of this dictionary (the Redis hash) to contain something other than a string, such as a

list or nested dictionary with strings as values? Here’s an example using some JSON-like data to make the distinction clearer:

restaurant_484272 = {

"name": "Ravagh",

"type": "Persian",

"address": {

"street": {

"line1": "11 E 30th St",

"line2": "APT 1",

},

"city": "New York",

"state": "NY",

"zip": 10016,

}

}

Say that we want to set a Redis hash with the key

484272 and field-value pairs corresponding to the key-value pairs from restaurant_484272 . Redis does not support this directly, because restaurant_484272 is nested:>>>

>>> r.hmset(484272, restaurant_484272)

Traceback (most recent call last):

# ...

redis.exceptions.DataError: Invalid input of type: 'dict'.

Convert to a byte, string or number first.

You can in fact make this work with Redis. There are two different ways to mimic nested data in

redis-py and Redis:- Serialize the values into a string with something like

json.dumps() - Use a delimiter in the key strings to mimic nesting in the values

Let’s take a look at an example of each.

Option 1:Serialize the Values Into a String

You can use

json.dumps() to serialize the dict into a JSON-formatted string:>>>

>>> import json

>>> r.set(484272, json.dumps(restaurant_484272))

True

If you call

.get() , the value you get back will be a bytes object, so don’t forget to deserialize it to get back the original object. json.dumps() and json.loads() are inverses of each other, for serializing and deserializing data, respectively:>>>

>>> from pprint import pprint

>>> pprint(json.loads(r.get(484272)))

{'address': {'city': 'New York',

'state': 'NY',

'street': '11 E 30th St',

'zip': 10016},

'name': 'Ravagh',

'type': 'Persian'}

This applies to any serialization protocol, with another common choice being

yaml :>>>

>>> import yaml # python -m pip install PyYAML

>>> yaml.dump(restaurant_484272)

'address: {city: New York, state: NY, street: 11 E 30th St, zip: 10016}\nname: Ravagh\ntype: Persian\n'

No matter what serialization protocol you choose to go with, the concept is the same:you’re taking an object that is unique to Python and converting it to a bytestring that is recognized and exchangeable across multiple languages.

Option 2:Use a Delimiter in Key Strings

There’s a second option that involves mimicking “nestedness” by concatenating multiple levels of keys in a Python

dict . This consists of flattening the nested dictionary through recursion, so that each key is a concatenated string of keys, and the values are the deepest-nested values from the original dictionary. Consider our dictionary object restaurant_484272 :restaurant_484272 = {

"name": "Ravagh",

"type": "Persian",

"address": {

"street": {

"line1": "11 E 30th St",

"line2": "APT 1",

},

"city": "New York",

"state": "NY",

"zip": 10016,

}

}

We want to get it into this form:

{

"484272:name": "Ravagh",

"484272:type": "Persian",

"484272:address:street:line1": "11 E 30th St",

"484272:address:street:line2": "APT 1",

"484272:address:city": "New York",

"484272:address:state": "NY",

"484272:address:zip": "10016",

}

That’s what

setflat_skeys() below does, with the added feature that it does inplace .set() operations on the Redis instance itself rather than returning a copy of the input dictionary: 1from collections.abc import MutableMapping

2

3def setflat_skeys(

4 r: redis.Redis,

5 obj: dict,

6 prefix: str,

7 delim: str = ":",

8 *,

9 _autopfix=""

10) -> None:

11 """Flatten `obj` and set resulting field-value pairs into `r`.

12

13 Calls `.set()` to write to Redis instance inplace and returns None.

14

15 `prefix` is an optional str that prefixes all keys.

16 `delim` is the delimiter that separates the joined, flattened keys.

17 `_autopfix` is used in recursive calls to created de-nested keys.

18

19 The deepest-nested keys must be str, bytes, float, or int.

20 Otherwise a TypeError is raised.

21 """

22 allowed_vtypes = (str, bytes, float, int)

23 for key, value in obj.items():

24 key = _autopfix + key

25 if isinstance(value, allowed_vtypes):

26 r.set(f"{prefix}{delim}{key}", value)

27 elif isinstance(value, MutableMapping):

28 setflat_skeys(

29 r, value, prefix, delim, _autopfix=f"{key}{delim}"

30 )

31 else:

32 raise TypeError(f"Unsupported value type: {type(value)}")

The function iterates over the key-value pairs of

obj , first checking the type of the value (Line 25) to see if it looks like it should stop recursing further and set that key-value pair. Otherwise, if the value looks like a dict (Line 27), then it recurses into that mapping, adding the previously seen keys as a key prefix (Line 28). Let’s see it at work:

>>>

>>> r.flushdb() # Flush database: clear old entries

>>> setflat_skeys(r, restaurant_484272, 484272)

>>> for key in sorted(r.keys("484272*")): # Filter to this pattern

... print(f"{repr(key):35}{repr(r.get(key)):15}")

...

b'484272:address:city' b'New York'

b'484272:address:state' b'NY'

b'484272:address:street:line1' b'11 E 30th St'

b'484272:address:street:line2' b'APT 1'

b'484272:address:zip' b'10016'

b'484272:name' b'Ravagh'

b'484272:type' b'Persian'

>>> r.get("484272:address:street:line1")

b'11 E 30th St'

The final loop above uses

r.keys("484272*") , where "484272*" is interpreted as a pattern and matches all keys in the database that begin with "484272" . Notice also how

setflat_skeys() calls just .set() rather than .hset() , because we’re working with plain string:string field-value pairs, and the 484272 ID key is prepended to each field string. Encryption

Another trick to help you sleep well at night is to add symmetric encryption before sending anything to a Redis server. Consider this as an add-on to the security that you should make sure is in place by setting proper values in your Redis configuration. The example below uses the

cryptography package:$ python -m pip install cryptography

To illustrate, pretend that you have some sensitive cardholder data (CD) that you never want to have sitting around in plaintext on any server, no matter what. Before caching it in Redis, you can serialize the data and then encrypt the serialized string using Fernet:

>>>

>>> import json

>>> from cryptography.fernet import Fernet

>>> cipher = Fernet(Fernet.generate_key())

>>> info = {

... "cardnum": 2211849528391929,

... "exp": [2020, 9],

... "cv2": 842,

... }

>>> r.set(

... "user:1000",

... cipher.encrypt(json.dumps(info).encode("utf-8"))

... )

>>> r.get("user:1000")

b'gAAAAABcg8-LfQw9TeFZ1eXbi' # ... [truncated]

>>> cipher.decrypt(r.get("user:1000"))

b'{"cardnum": 2211849528391929, "exp": [2020, 9], "cv2": 842}'

>>> json.loads(cipher.decrypt(r.get("user:1000")))

{'cardnum': 2211849528391929, 'exp': [2020, 9], 'cv2': 842}

Because

info contains a value that is a list , you’ll need to serialize this into a string that’s acceptable by Redis. (You could use json , yaml , or any other serialization for this.) Next, you encrypt and decrypt that string using the cipher objeto. You need to deserialize the decrypted bytes using json.loads() so that you can get the result back into the type of your initial input, a dict . Observação :Fernet uses AES 128 encryption in CBC mode. See the

cryptography docs for an example of using AES 256. Whatever you choose to do, use cryptography , not pycrypto (imported as Crypto ), which is no longer actively maintained. If security is paramount, encrypting strings before they make their way across a network connection is never a bad idea.

Compression

One last quick optimization is compression. If bandwidth is a concern or you’re cost-conscious, you can implement a lossless compression and decompression scheme when you send and receive data from Redis. Here’s an example using the bzip2 compression algorithm, which in this extreme case cuts down on the number of bytes sent across the connection by a factor of over 2,000:

>>>

1>>> import bz2

2

3>>> blob = "i have a lot to talk about" * 10000

4>>> len(blob.encode("utf-8"))

5260000

6

7>>> # Set the compressed string as value

8>>> r.set("msg:500", bz2.compress(blob.encode("utf-8")))

9>>> r.get("msg:500")

10b'BZh91AY&SY\xdaM\x1eu\x01\x11o\x91\x80@\x002l\x87\' # ... [truncated]

11>>> len(r.get("msg:500"))

12122

13>>> 260_000 / 122 # Magnitude of savings

142131.1475409836066

15

16>>> # Get and decompress the value, then confirm it's equal to the original

17>>> rblob = bz2.decompress(r.get("msg:500")).decode("utf-8")

18>>> rblob == blob

19True

The way that serialization, encryption, and compression are related here is that they all occur client-side. You do some operation on the original object on the client-side that ends up making more efficient use of Redis once you send the string over to the server. The inverse operation then happens again on the client side when you request whatever it was that you sent to the server in the first place.

Using Hiredis

It’s common for a client library such as

redis-py to follow a protocol in how it is built. In this case, redis-py implements the REdis Serialization Protocol, or RESP. Part of fulfilling this protocol consists of converting some Python object in a raw bytestring, sending it to the Redis server, and parsing the response back into an intelligible Python object.

For example, the string response “OK” would come back as

"+OK\r\n" , while the integer response 1000 would come back as ":1000\r\n" . This can get more complex with other data types such as RESP arrays. A parser is a tool in the request-response cycle that interprets this raw response and crafts it into something recognizable to the client.

redis-py ships with its own parser class, PythonParser , which does the parsing in pure Python. (See .read_response() if you’re curious.) However, there’s also a C library, Hiredis, that contains a fast parser that can offer significant speedups for some Redis commands such as

LRANGE . You can think of Hiredis as an optional accelerator that it doesn’t hurt to have around in niche cases. All that you have to do to enable

redis-py to use the Hiredis parser is to install its Python bindings in the same environment as redis-py :$ python -m pip install hiredis

What you’re actually installing here is

hiredis-py , which is a Python wrapper for a portion of the hiredis C library. The nice thing is that you don’t really need to call

hiredis você mesma. Just pip install it, and this will let redis-py see that it’s available and use its HiredisParser instead of PythonParser . Internally,

redis-py will attempt to import hiredis , and use a HiredisParser class to match it, but will fall back to its PythonParser instead, which may be slower in some cases:# redis/utils.py

try:

import hiredis

HIREDIS_AVAILABLE = True

except ImportError:

HIREDIS_AVAILABLE = False

# redis/connection.py

if HIREDIS_AVAILABLE:

DefaultParser = HiredisParser

else:

DefaultParser = PythonParser

Using Enterprise Redis Applications

While Redis itself is open-source and free, several managed services have sprung up that offer a data store with Redis as the core and some additional features built on top of the open-source Redis server:

-

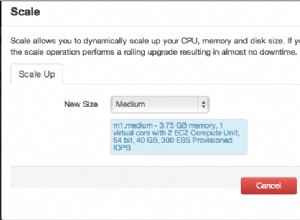

Amazon ElastiCache for Redis : This is a web service that lets you host a Redis server in the cloud, which you can connect to from an Amazon EC2 instance. For full setup instructions, you can walk through Amazon’s ElastiCache for Redis launch page.

-

Microsoft’s Azure Cache for Redis : This is another capable enterprise-grade service that lets you set up a customizable, secure Redis instance in the cloud.

The designs of the two have some commonalities. You typically specify a custom name for your cache, which is embedded as part of a DNS name, such as

demo.abcdef.xz.0009.use1.cache.amazonaws.com (AWS) or demo.redis.cache.windows.net (Azure). Once you’re set up, here are a few quick tips on how to connect.

From the command line, it’s largely the same as in our earlier examples, but you’ll need to specify a host with the

h flag rather than using the default localhost. For Amazon AWS , execute the following from your instance shell:$ export REDIS_ENDPOINT="demo.abcdef.xz.0009.use1.cache.amazonaws.com"

$ redis-cli -h $REDIS_ENDPOINT

For Microsoft Azure , you can use a similar call. Azure Cache for Redis uses SSL (port 6380) by default rather than port 6379, allowing for encrypted communication to and from Redis, which can’t be said of TCP. All that you’ll need to supply in addition is a non-default port and access key:

$ export REDIS_ENDPOINT="demo.redis.cache.windows.net"

$ redis-cli -h $REDIS_ENDPOINT -p 6380 -a <primary-access-key>

The

-h flag specifies a host, which as you’ve seen is 127.0.0.1 (localhost) by default. When you’re using

redis-py in Python, it’s always a good idea to keep sensitive variables out of Python scripts themselves, and to be careful about what read and write permissions you afford those files. The Python version would look like this:>>>

>>> import os

>>> import redis

>>> # Specify a DNS endpoint instead of the default localhost

>>> os.environ["REDIS_ENDPOINT"]

'demo.abcdef.xz.0009.use1.cache.amazonaws.com'

>>> r = redis.Redis(host=os.environ["REDIS_ENDPOINT"])

That’s all there is to it. Besides specifying a different

host , you can now call command-related methods such as r.get() as normal. Observação :If you want to use solely the combination of

redis-py and an AWS or Azure Redis instance, then you don’t really need to install and make Redis itself locally on your machine, since you don’t need either redis-cli or redis-server . If you’re deploying a medium- to large-scale production application where Redis plays a key role, then going with AWS or Azure’s service solutions can be a scalable, cost-effective, and security-conscious way to operate.

Wrapping Up

That concludes our whirlwind tour of accessing Redis through Python, including installing and using the Redis REPL connected to a Redis server and using

redis-py in real-life examples. Here’s some of what you learned:redis-pylets you do (almost) everything that you can do with the Redis CLI through an intuitive Python API.- Mastering topics such as persistence, serialization, encryption, and compression lets you use Redis to its full potential.

- Redis transactions and pipelines are essential parts of the library in more complex situations.

- Enterprise-level Redis services can help you smoothly use Redis in production.

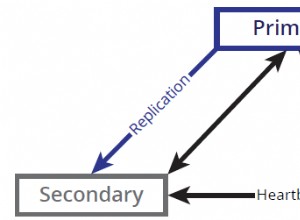

Redis has an extensive set of features, some of which we didn’t really get to cover here, including server-side Lua scripting, sharding, and master-slave replication. If you think that Redis is up your alley, then make sure to follow developments as it implements an updated protocol, RESP3.

Further Reading

Here are some resources that you can check out to learn more.

Books:

- Josiah Carlson: Redis in Action

- Karl Seguin: The Little Redis Book

- Luc Perkins et. al.: Seven Databases in Seven Weeks

Redis in use:

- Twitter: Real-Time Delivery Architecture at Twitter

- Spool: Redis bitmaps – Fast, easy, realtime metrics

- 3scale: Having fun with Redis Replication between Amazon and Rackspace

- Instagram: Storing hundreds of millions of simple key-value pairs in Redis

- Craigslist: Redis Sharding at Craigslist

- Disqus: Redis at Disqus

Other:

- Digital Ocean: How To Secure Your Redis Installation

- AWS: ElastiCache for Redis User Guide

- Microsoft: Azure Cache for Redis

- Cheatography: Redis Cheat Sheet

- ClassDojo: Better Rate Limiting With Redis Sorted Sets

- antirez (Salvatore Sanfilippo): Redis persistence demystified

- Martin Kleppmann: How to do distributed locking

- HighScalability: 11 Common Web Use Cases Solved in Redis